A musical called four is the work of theoretical theatre* I’m currently sharing. Click here for the start of the story.

Here is the daughter.

(She doesn’t have to be the daughter. She doesn’t have to be a ‘she’. In that sense, imagine the character any way it works for you.)

I’ve never really understood how to human.

Until the neurodivergence diagnosis in my late forties, I didn’t even realise that I didn’t understand. Since the diagnosis, I’ve come a long way. With those I trust the most, who most trust me, I can now say at times, “Before you tell me this story, please be clear about whether you are happy about it, or sad, or angry, or something else, so I can know how best to respond.”

I consider this to be breaking the fourth wall. You’re not supposed to ask. You’re just supposed to know. You grow, and the knowing grows. That’s how it’s s’posed to go. Except… no.

Being neurodivergent is a cacophonous existence.

Before you know that this applies to you, life can feel like a barrage of continuous yelling up and down the stairs.

People want things from you, and it's hard to tell what, and it all sounds urgent and you've got no clue what's going on but they seem to say you're doing something wrong in the stupidest of ways. Add a chorus of reactionary noise — snorts, laughs with rolling eyes, gasps, sympathetic sighs — if you try to ask for clarity or charity. Not to mention there are voices in your head second-guessing you. What I thought was personality — the slowly grown discovery of me — turned out to be some very loud acquired insecurities, all terrified and angry and all fighting for the lead by changing key and changing key and changing key. So you try to listen to the past, to what last worked relatively well, sort through bellowing memories with ruddy faces and sallow memories with bloody noses and mellowing memories with yellow bruises turning brown and you turn them all down in the search for whatever last didn't hurt you. Anything you did that got you through and out the other side. Something... reliable. Even if you don't know why. Oh, there they are, look: sound-drowned father, angry son, and scrambling mother, and above the noise above their heads, up by the sky: silence

There are times when I’m silent because I need to think. Because I can’t answer you until I’ve had the chance to think, but you are still going, and I am waiting for silence.

… or I’ll give you an answer shaped by what I believe is expected, acceptable, typical. It’s so instinctive that I probably believe it’s truthful, in the moment. Then I’m immediately moving on, anticipating the next challenge, continuously figuring out the next expected, acceptable, typical behaviour. Conversations move fast: you have no idea. Plus, there are unexpected trip hazards fucking everywhere.

If you want to know how I really feel, I probably need to think.

There are some times when I’m silent because I cannot speak.

I get stuck. There are words in my head — often shouting in my head — and I’m certain of them, but I can’t. I just can’t. I can’t anything. Everything is too big.

This is one of the reasons why I find the whole ‘characters sing when they can’t speak’ thing frustrating: it’s a very neurotypical assumption. Sometimes everything is so big for me that I can only silence.

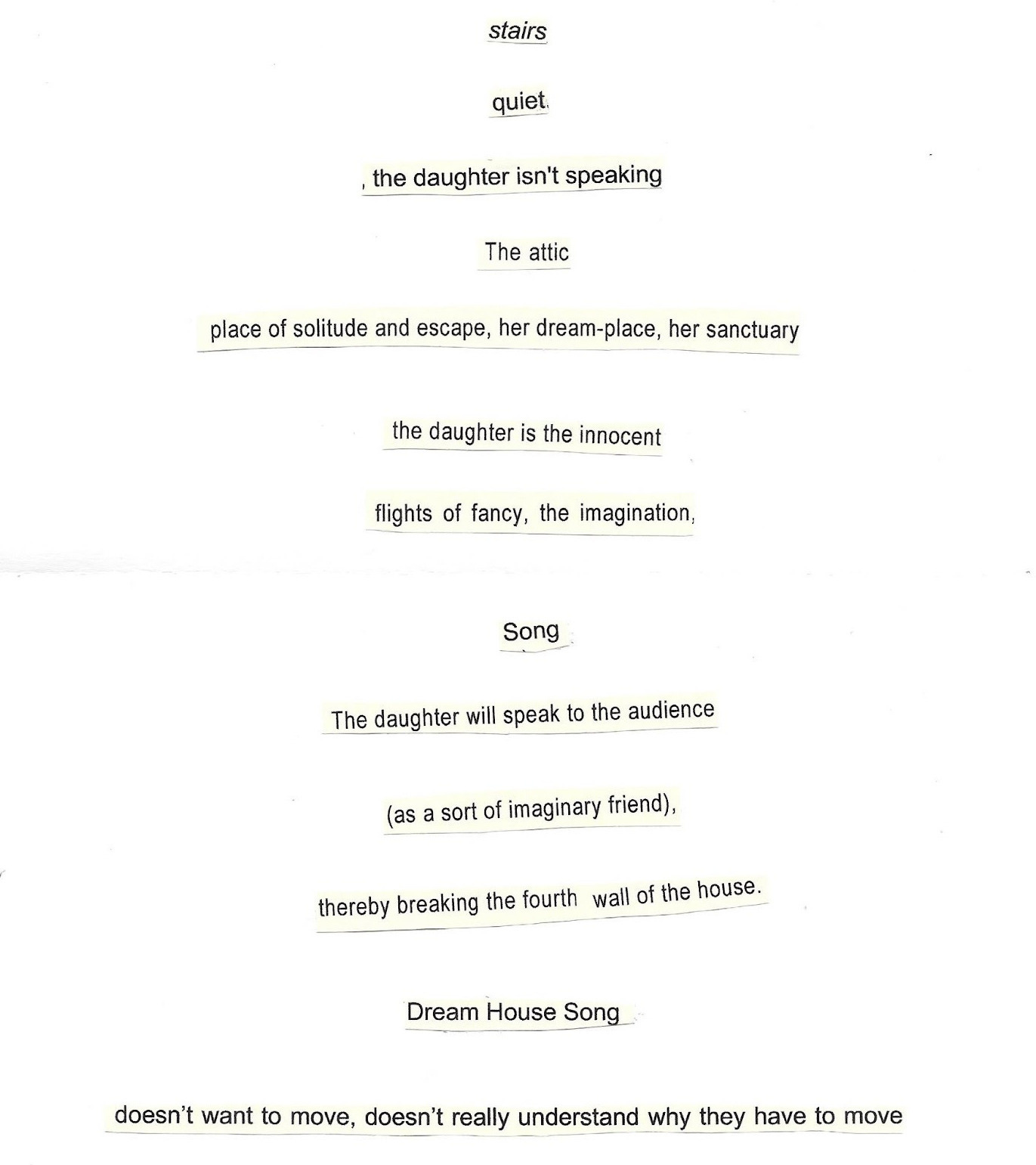

The daughter needs to think. She doesn’t want to move house (or move from sitting still) and she doesn’t understand why they need to move house. Let’s not mistake that for a decision: she needs to think about it.

Maybe she’s up there waiting until she’s even able to think, but everything is noise and everything is stairs and doors and everything is stuff and it’s a lot. There are unexpected trip hazards everywhere.

Being able to think needs focus, perhaps for all of us, if we want to do it truly, no matter how our brain works. After all, if you’re responding to someone, you must

take into consideration the continuation of the conversation. What about companionless communication?

When I was a child, I would see characters on stage breaking the fourth wall and speaking directly to the audience, and it felt as if we were their secret friends: people in whom they could safely confide without fear of being rushed on in conversation.

They are able to be fully honest, able to stop and think about how they felt, stop and consider what to do, and even make observations about the outcome.

When I need to think about how I feel, I can sometimes talk it out… if there’s someone who is happy to let me talk it out, that is. To listen to me curiously, which is not the same as a conversation. It’s also not what a typical audience does, but we are on the fringes of monologue, soliloquy.

For what is the I Want song, if not having a moment to think out loud about how one feels, and declare it? What is the 11 o’clock number, if not an out loud summary of outcome?

When I was young, these things seemed to me incredibly useful systems to which we non-characters had neither access nor equivalent — which is much to do with why I make what I call ‘included’ theatre, where we can be included in the systems as much as included in the story world. (And it’s better for me if there is accompanied rather than latent listening, but more of that later. Or elsewhere.)

My notes say “Song”. They also say that the daughter will speak to the audience. These are notes from the writer I was twenty-five years ago, when I was studying the craft.

This musical was designed to explore the ‘voice’ of composition, using a different composer for each character. It seems to me a youthful, innocent exploration now. I’m still interested in voice and sound, though perhaps… more openly. I broke the fourth wall of theatre-making long ago. I’m not sure there are any walls for me at all now: voice is sound is song is speech is silence.

In The Poetics of Space, Bachelard says:

“The French baritone, Charles Panzera, who is sensitive to poetry, once told me that, according to certain experimental psychologists, it is impossible to think the vowel sound ‘ah’ without a tautening of the vocal chords. In other words, we read ah and the voice is ready to sing… And when I let my nonconformist philosopher’s daydreams go unchecked, I begin to think that the vowel ‘a’ is the vowel of immensity. It is a sound area that starts with a sigh and extends beyond all limits.”

In my spectrum of fear ← anger — relief → hunger, the son constricts with anger, but the daughter opens up with relief.

Silence starts with a sigh.

Silence… In theory, find silence for yourself and sigh. In theory, extend time and space up high, near the sky. In theory, linger, occupy.

There is more to the daughter, but that will come later.

Click here to read the previous post: father

Click here to read the next one: connection

*This may be theoretical theatre, but it’s still protected by Copyright © 2000-2025 by Jenifer Toksvig All Rights Reserved. Though I may be inspired by conversation and ideas, as long as you don’t infringe my copyright, anything you write in response to this belongs to you. Obviously. The Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard is translated into English by Maria Jolas, quoted here where referenced for the purposes of researching this work.

this brings to mind something that Artaud wrote "il importe avant tout de rompre l'assujettissement du théâtre au texte, et de retrouver la notion d'une sorte de langage unique à mi-chemin entre la geste et la pensée" I've spent a good deal of my life living amongst insane people. Whether or not I'm insane is a matter of diagnosis. I wrote a screenplay about a young schizophrenic who becomes a an indy music star after having a psychotic episode on the Venice Beach boardwalk. Nobody was interested. I don't know why not. It was inspired in part by a neighbor I had when I lived in the Hotel Cecil. Some people in Los Angeles understand that the Hotel Cecil has great cultural importance but none of them understand how it has cultural importance. For that you have to live in the place.